Curator St John Simpson explains how the Museum is helping to fight the contemporary trade of looted antiquities across the globe.

Publish dateWednesday 13 November 2019 - 14:44

Story Code : 195522

In 2001 the Taliban government of Afghanistan banned all representations of the human form, from depictions on TV and in painting to ancient sculpture. Statues in the National Museum of Afghanistan were decapitated and the famous Buddhas of Bamiyan were blown up. Many other ancient monuments across the country were also damaged at this time and it was probably during these months that another group of beautiful Buddhist sculptures was deliberately broken. Local dealers were afraid to handle such objects, but once the Taliban were overthrown later that year, these pieces were collected and smuggled out via Pakistan.

The looting of archaeological sites is a huge problem around the world and is particularly bad during periods of economic and political crisis. The British Museum works very closely with UK law enforcement agencies and countries worldwide to help fight the illicit export and sale of antiquities on the black market. Since 2009 the Museum has helped return 2,345 objects to Afghanistan, Iraq and Uzbekistan – mostly the result of illegal trafficking. This includes the identification, cataloguing and return of thousands of antiquities of all periods to Afghanistan, many others to Iraq and a monumental glazed medieval tile to Uzbekistan. A few weeks ago the Museum opened a new changing case display at the top of the East Stairs (Room 53) which focuses on this work. The first to be displayed are those very same Buddhist sculptures from Afghanistan that were damaged almost two decades ago. They will be on display until late December and then be returned to the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

Seized Buddhist sculptures go on temporary display in a case in Room 53.

The sculptures were seized in the UK as part of an operation involving the Art and Antiques Unit of the Metropolitan Police and brought to the Museum for identification. They date from between the fourth and sixth centuries AD when Buddhism was the main religion in Afghanistan and the region was first under the rule of the Sasanian empire, centred on present-day Iran and Iraq.

The largest sculpture is carved from grey schist (a type of stone) and is of a princely figure wearing elaborate necklaces with a so-called ‘wet drapery’ carving effect seen on his clinging robes. He is a bodhisattva – a person who wishes to become as enlightened as Buddha. The material and style are typical of the Gandhara region of present-day Swat in Pakistan but such pieces were exported in antiquity and set up in monasteries as far away as Merv in present-day Turkmenistan.

Gandharan sculpture of a male bodhisattva.

The nine other pieces that were seized are made of coarse clay wrapped in a finer material resembling stucco plaster which has been finely modelled and painted. They are mostly representations of bodhisattvas, some wearing elaborate diadems (crowns) and shown in a variety of styles. They closely resemble pieces excavated in monasteries at Hadda, near Jalalabad, and on one of the key routes connecting Afghanistan with Pakistan, via the Khyber Pass. However, it is not known where exactly the present pieces were found and another possibility is that they come from illicit excavations at one of the ancient monasteries in the Mes Aynak area south of Kabul.

Rescue excavations in this area have revealed spectacular remains, including a polychrome Gandharan schist sculpture, the first wooden carving of a Buddha from this period, and many painted clay and stucco representations in different styles. There is an enticing angle to this possibility, as this is one of the areas where the late Osama bin Laden is rumoured to have been headquartered – Buddhist art would hardly have been tolerated and it was as a result of his influence that the Taliban hardened their attitudes to figural imagery in 2001.

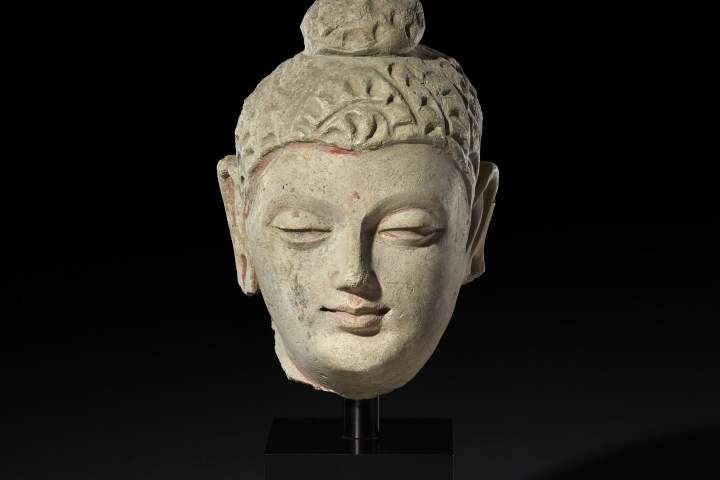

Moulded and painted clay head of a female bodhisattva wearing a diadem (crown).

CT scans – conducted by the Museum’s Department of Conservation and Scientific Research – have revealed how these heads were made, and scientific analysis shows that the red and yellow pigments found on the heads were made from common iron-rich ores. Such sculptures were commonly painted but so far there has not been much scientific work published on the subject. The rediscovery of the sculptures was a good opportunity to conduct this work and we are very grateful to the National Museum of Afghanistan for permitting us to do so.

An X-ray CT scan of the head reveals a two-layered construction: a coarse clay was used to roughly model the shape of the head. The face, hair and headdress were overlaid with a finer and more compact material which was then painted.

Scientific analyses showed that a red paint, rich in iron oxide, was applied over a carbon black layer to deepen the hue. The right image shows how enhancement techniques help visualise the remains of this paint.

The British Museum has a long and strong relationship with the National Museum of Afghanistan as our experts helped to build their first conservation laboratory and, in 2009, we returned more than three tons of antiquities seized in the UK over several years. These ranged from third-millennium-BC bronze cosmetic containers and other objects looted from Bronze Age cemeteries in northern Afghanistan (known as Bactria) to medieval metalware looted from other sites.

Some of these objects were put on display soon after in the National Museum of Afghanistan’s newly restored galleries. Discussions continued and in 2011 I curated a very successful exhibition called Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World. It was humbling to work with their curators and conservators as these were some of the people known as key-holders who had moved and concealed their most valuable objects during the dreadful civil war of 1992–1994 and kept their location secret until the Taliban government was overthrown and the government of former President Hamid Karzai installed in December 2001. When we were installing some of the loaned objects, the director and staff of the National Museum of Afghanistan gave permission for us to scientifically analyse some of the loans and the British Museum also signed an agreement pledging co-operation over the identification and return of looted or stolen antiquities.

Main entrance of the fully restored National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

That year, thanks to the generosity of the art dealer John Eskenazi and additional support from the exhibition sponsor Bank of America Merrill Lynch as part of its Art Conservation Project, we were also able to accept, conserve, analyse and exhibit a spectacular group of 20 carved ivory and bone furniture overlays. These date to the first century AD and had been excavated in the 1940s by a French expedition to the ancient city at Begram. These had been stolen from the museum in Kabul during the civil war and had previously been feared lost forever. We published a small book on these pieces, as well as two journal articles and a long monograph, and sent the objects back to Kabul in 2012, where they are safe.

While we were getting ready for President Karzai to open this exhibition, we were told of the whereabouts of another famous stolen antiquity. This is popularly known as the ‘fire Buddha’ and is a monumental sculpture found in 1965 at Sarai Khuja, north of Kabul. It was exhibited in the museum in Kabul until it was wrenched from the wall one night in 1996. It transpired that it had entered a private collection in Japan and, after much discussion, it was very generously acquired on behalf of the National Museum of Afghanistan by John Eskenazi who presented it in memory of the late Carla Grissman (1928–2011), who did much to work with the Afghan museum staff and who was one of the founding members of SPACH (Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage).

The ‘fire Buddha’ goes on display on the main staircase in the National Museum of Afghanistan. © Andy Miller.

Since then we have continued to keep a vigilant eye open for other objects which could have come to the UK illegally from Afghanistan. In 2015 a German couple, Patrick and Paola von Aulock, offered to sell (through Christie’s auction house) a decorated tinned copper wine-bowl dated by its inscription to the year 1604–1605. Christie’s quickly identified it as having been catalogued and published, as early as 1974, as being part of the Kabul museum collection. As the owners had bought it in 1994 from an Afghan dealer in Jeddah, it must have quickly made its way there soon after the civil war looting of the museum after 1992. The owners generously agreed to present it back to the National Museum of Afghanistan, where it is now on display in their new Islamic gallery.

The British Museum’s current display in Room 53 is the latest episode in this story – watch this space for the latest developments.

To find out more about objects from Afghanistan and the return of looted antiquities, take a look at these publications:

The looting of archaeological sites is a huge problem around the world and is particularly bad during periods of economic and political crisis. The British Museum works very closely with UK law enforcement agencies and countries worldwide to help fight the illicit export and sale of antiquities on the black market. Since 2009 the Museum has helped return 2,345 objects to Afghanistan, Iraq and Uzbekistan – mostly the result of illegal trafficking. This includes the identification, cataloguing and return of thousands of antiquities of all periods to Afghanistan, many others to Iraq and a monumental glazed medieval tile to Uzbekistan. A few weeks ago the Museum opened a new changing case display at the top of the East Stairs (Room 53) which focuses on this work. The first to be displayed are those very same Buddhist sculptures from Afghanistan that were damaged almost two decades ago. They will be on display until late December and then be returned to the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

Seized Buddhist sculptures go on temporary display in a case in Room 53.

The sculptures were seized in the UK as part of an operation involving the Art and Antiques Unit of the Metropolitan Police and brought to the Museum for identification. They date from between the fourth and sixth centuries AD when Buddhism was the main religion in Afghanistan and the region was first under the rule of the Sasanian empire, centred on present-day Iran and Iraq.

The largest sculpture is carved from grey schist (a type of stone) and is of a princely figure wearing elaborate necklaces with a so-called ‘wet drapery’ carving effect seen on his clinging robes. He is a bodhisattva – a person who wishes to become as enlightened as Buddha. The material and style are typical of the Gandhara region of present-day Swat in Pakistan but such pieces were exported in antiquity and set up in monasteries as far away as Merv in present-day Turkmenistan.

Gandharan sculpture of a male bodhisattva.

The nine other pieces that were seized are made of coarse clay wrapped in a finer material resembling stucco plaster which has been finely modelled and painted. They are mostly representations of bodhisattvas, some wearing elaborate diadems (crowns) and shown in a variety of styles. They closely resemble pieces excavated in monasteries at Hadda, near Jalalabad, and on one of the key routes connecting Afghanistan with Pakistan, via the Khyber Pass. However, it is not known where exactly the present pieces were found and another possibility is that they come from illicit excavations at one of the ancient monasteries in the Mes Aynak area south of Kabul.

Rescue excavations in this area have revealed spectacular remains, including a polychrome Gandharan schist sculpture, the first wooden carving of a Buddha from this period, and many painted clay and stucco representations in different styles. There is an enticing angle to this possibility, as this is one of the areas where the late Osama bin Laden is rumoured to have been headquartered – Buddhist art would hardly have been tolerated and it was as a result of his influence that the Taliban hardened their attitudes to figural imagery in 2001.

Moulded and painted clay head of a female bodhisattva wearing a diadem (crown).

CT scans – conducted by the Museum’s Department of Conservation and Scientific Research – have revealed how these heads were made, and scientific analysis shows that the red and yellow pigments found on the heads were made from common iron-rich ores. Such sculptures were commonly painted but so far there has not been much scientific work published on the subject. The rediscovery of the sculptures was a good opportunity to conduct this work and we are very grateful to the National Museum of Afghanistan for permitting us to do so.

An X-ray CT scan of the head reveals a two-layered construction: a coarse clay was used to roughly model the shape of the head. The face, hair and headdress were overlaid with a finer and more compact material which was then painted.

Scientific analyses showed that a red paint, rich in iron oxide, was applied over a carbon black layer to deepen the hue. The right image shows how enhancement techniques help visualise the remains of this paint.

The British Museum has a long and strong relationship with the National Museum of Afghanistan as our experts helped to build their first conservation laboratory and, in 2009, we returned more than three tons of antiquities seized in the UK over several years. These ranged from third-millennium-BC bronze cosmetic containers and other objects looted from Bronze Age cemeteries in northern Afghanistan (known as Bactria) to medieval metalware looted from other sites.

Some of these objects were put on display soon after in the National Museum of Afghanistan’s newly restored galleries. Discussions continued and in 2011 I curated a very successful exhibition called Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World. It was humbling to work with their curators and conservators as these were some of the people known as key-holders who had moved and concealed their most valuable objects during the dreadful civil war of 1992–1994 and kept their location secret until the Taliban government was overthrown and the government of former President Hamid Karzai installed in December 2001. When we were installing some of the loaned objects, the director and staff of the National Museum of Afghanistan gave permission for us to scientifically analyse some of the loans and the British Museum also signed an agreement pledging co-operation over the identification and return of looted or stolen antiquities.

Main entrance of the fully restored National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

That year, thanks to the generosity of the art dealer John Eskenazi and additional support from the exhibition sponsor Bank of America Merrill Lynch as part of its Art Conservation Project, we were also able to accept, conserve, analyse and exhibit a spectacular group of 20 carved ivory and bone furniture overlays. These date to the first century AD and had been excavated in the 1940s by a French expedition to the ancient city at Begram. These had been stolen from the museum in Kabul during the civil war and had previously been feared lost forever. We published a small book on these pieces, as well as two journal articles and a long monograph, and sent the objects back to Kabul in 2012, where they are safe.

While we were getting ready for President Karzai to open this exhibition, we were told of the whereabouts of another famous stolen antiquity. This is popularly known as the ‘fire Buddha’ and is a monumental sculpture found in 1965 at Sarai Khuja, north of Kabul. It was exhibited in the museum in Kabul until it was wrenched from the wall one night in 1996. It transpired that it had entered a private collection in Japan and, after much discussion, it was very generously acquired on behalf of the National Museum of Afghanistan by John Eskenazi who presented it in memory of the late Carla Grissman (1928–2011), who did much to work with the Afghan museum staff and who was one of the founding members of SPACH (Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage).

The ‘fire Buddha’ goes on display on the main staircase in the National Museum of Afghanistan. © Andy Miller.

Since then we have continued to keep a vigilant eye open for other objects which could have come to the UK illegally from Afghanistan. In 2015 a German couple, Patrick and Paola von Aulock, offered to sell (through Christie’s auction house) a decorated tinned copper wine-bowl dated by its inscription to the year 1604–1605. Christie’s quickly identified it as having been catalogued and published, as early as 1974, as being part of the Kabul museum collection. As the owners had bought it in 1994 from an Afghan dealer in Jeddah, it must have quickly made its way there soon after the civil war looting of the museum after 1992. The owners generously agreed to present it back to the National Museum of Afghanistan, where it is now on display in their new Islamic gallery.

The British Museum’s current display in Room 53 is the latest episode in this story – watch this space for the latest developments.

To find out more about objects from Afghanistan and the return of looted antiquities, take a look at these publications:

avapress.net/vdcdxk0fxyt0nk6.em2y.html

Top hits