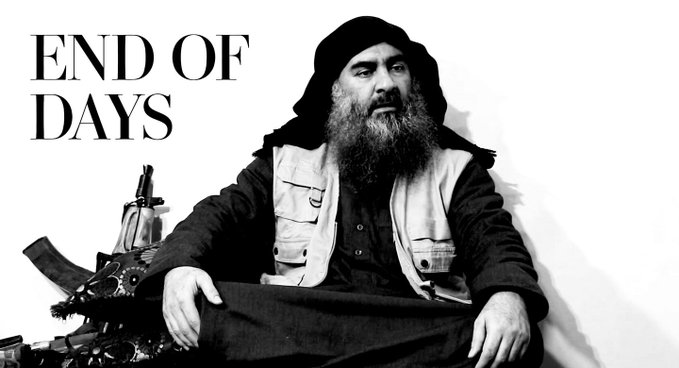

In President Trump’s unique vocabulary, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the extremist leader of the Islamic State whom thousands of followers hailed as “caliph,” died “like a dog … whimpering, crying, screaming” beneath a compound in northwestern Syria. Trump shared the news of Baghdadi’s death in a televised announcement from the White House on Sunday morning following a nighttime operation carried out by elite U.S. forces Saturday.

Publish dateMonday 28 October 2019 - 16:24

Story Code : 194156

“Last night the United States brought the world’s Number One terrorist leader to justice,” Trump said, referring to the once-obscure religious scholar turned rapist and genocidal warlord. “He was a sick and depraved man, and now he’s gone.”

According to Trump, Baghdadi exploded a suicide vest after being cornered in a dead-end tunnel beneath a compound in Syria’s Idlib province where he and a number of comrades were staying. The U.S. president said that the detonation took the lives of Baghdadi, 48, and three of his children. A White House news release said that no U.S. personnel were lost in the operation, while five “enemy combatants” were killed in the compound and an unspecified number of “additional enemies” were slain in “the vicinity” of Baghdadi’s hideout.

“Trump described a harrowing operation that involved firefights before and after U.S. personnel, ferried under the cover of darkness in eight helicopters, touched down in Idlib,” my colleagues reported. “Officials said the military had taken DNA samples from Baghdadi’s remains and had quickly conducted visual and DNA tests to determine his identity. Nearly a dozen children were removed from the site, the president said. It was not clear where they were taken.”

How did this come about?

The details surrounding the operation are still emerging. According to reporting from my colleagues, “troops from Delta Force, an elite military unit, conducted the operation from a base in Iraq with support from the CIA and Kurdish forces.” Trump said the mission started around two weeks ago, though a leading Syrian Kurdish official claimed that Kurdish forces had been assisting in determining Baghdadi’s whereabouts for the past half a year. A senior official from Iraq’s intelligence service told The Post that arrests and interrogations carried out by Iraqi agents also helped yield Baghdadi’s location.

On Sunday, Trump hailed the work of U.S. intelligence agencies, taking credit for acting on their efforts to track down the militant leader. It marked a departure from his almost routine attacks on the supposed “deep state.” During his presidency, Trump has challenged the conclusions drawn by a host of career national security and intelligence officials on everything from Russian interference in the 2016 elections to the assassination of Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi to the White House’s potential abuses of power that are now at the heart of the ongoing impeachment inquiry.

According to the New York Times, the operation to take out Baghdadi was almost derailed by the president’s recent efforts to suddenly pull U.S. forces out of northern Syria. “Trump’s abrupt decision to withdraw American forces from northern Syria disrupted the meticulous planning and forced Pentagon officials to press ahead with a risky, night raid before their ability to control troops and spies and reconnaissance aircraft disappeared, according to military, intelligence and counterterrorism officials,” noted the Times. “Baghdadi’s death, they said, occurred largely in spite of Trump’s actions.”

Is this a game changer in the war against the Islamic State?

At the time of writing, the Islamic State had not confirmed Baghdadi’s death via its online channels. But his grisly, humiliating demise is at least a symbolic blow for the extremist group, which anchored much of its propaganda on the apocalyptic, messianic allure surrounding Baghdadi. In 2014 he declared the advent of a new Islamic “caliphate” from the pulpit of a historic mosque in the Iraqi city of Mosul and placed himself at the head of a blood-soaked theocratic pseudo-state that slaughtered, enslaved, and brutalized the populations caught under its sway. Half a decade later, though, the Islamic State is no longer a territorial power and exists largely in decentralized cells, scattered across rural towns in Syria and Iraq.

Analysts say these cells are largely autonomous and self-financing and may not suffer much from the decapitation of the organization’s leadership. The past two decades of U.S. covert action against Islamist extremists have seen a parade of militant leaders killed, only for their militant groups to endure. “In the annals of modern counterterrorism so far, what history has shown is these types of strikes do not lead to the strategic collapse or organizational defeat of a terrorism organization,” Javed Ali, a former White House counterterrorism director, told my colleague Liz Sly.

But it raises more questions about the militants’ ability to regroup and remain a threat. “Their recovery has been very slow, their organization is fragile and the killing of Baghdadi is bad timing for them,” Hassan Hassan of the Center for Global Policy told Sly. “Even though they have likely prepared for this moment, it will be hard for them to ensure the organization remains intact.”

Much of what happens next will be dictated by the shifting facts on the ground. As my colleagues reported in 2015, Baghdadi’s rise would have been impossible without the dismantling of the Baathist regime of Saddam Hussein that followed the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. A host of jobless, disaffected former Baathist officials made their way into the middle and upper ranks of Baghdadi’s outfit, forming a vanguard that helped the group seize almost a third of Iraq’s territory at its peak. With Syria still under a fog of war and mass political unrest gripping Iraq, the conditions for a revival remain.

What does this mean for Trump’s Syria policy?

From the dais at the White House, Trump thanked governments in Russia, Turkey, Iraq and even the Syrian regime for their tacit cooperation as the United States carried out the raid. He only briefly gestured to the assistance provided by the Syrian Democratic Forces. The Kurdish-led alliance provided the main boots on the ground during American’s campaign against the Islamic State but is also a faction viewed as a terrorist group by Turkey. SDF officials on Sunday claimed they had acted in concert with U.S. forces to also locate and target Baghdadi’s right-hand man and main spokesman in a town along the Turkish border.

Trump seemed more eager to return to his narrative of withdrawal, repeating both his somewhat historically dubious position that the Turks, Kurds and others were doomed to eternal war as well as his unorthodox insistence on “keeping” Middle Eastern oil — in this instance, a deployment of U.S. troops to garrison Syria’s eastern oil fields. “They’ve been fighting for hundreds of years,” Trump said of regional actors. “We’re out. But we are leaving soldiers to secure the oil. And we may have to fight for the oil. It’s okay. Maybe somebody else wants the oil, in which case they’ll have a hell of a fight.”

Counterterrorism experts shake their heads at such baldly imperialist posturing at a time when the United States could be consolidating its gains against Baghdadi’s organization. “The mission,” wrote Brett McGurk, a former top U.S. envoy to the anti-Islamic State coalition, “had been and should have remained to ensure Islamic State cannot reconstitute, not to protect an oil field once it does.”

Source : washingtonpost

avapress.net/vdcftjdyvw6d1ya.r7iw.html

Tags

Top hits