A probe launched by NASA four days after Elvis died has delivered a treasure trove of data from beyond the “solar bubble” that envelops Earth and our neighboring planets, scientists reported Monday.

Publish dateTuesday 5 November 2019 - 01:45

Story Code : 194765

But for every mystery Voyager 2 has solved about the solar winds, magnetic fields and cosmic rays that buffet the boundary between interstellar space and the Sun's sphere of influence, a new one has cropped up.

Voyager 2 left Earth's orbit in 1977 a month before its twin Voyager 1, but took seven years longer to reach the heliosphere's outer limit some 18 billion kilometers (more than 11 billion miles) away.

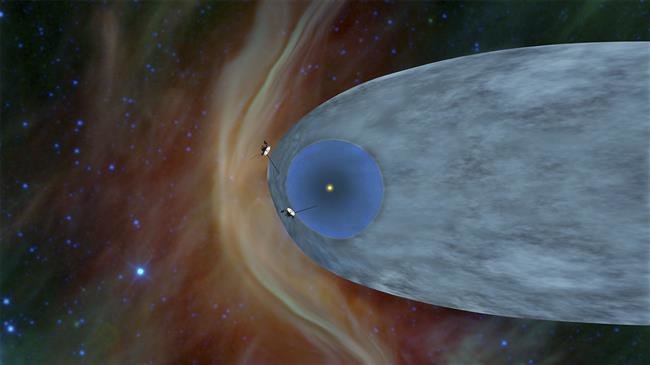

Shaped something like a windsock in a stiff breeze, the heliosphere is formed by the Sun's magnetic field and solar winds that can reach speeds of three million kilometers per hour.

It can be compared to a cosmic supertanker ploughing through space, said Edward Stone, a professor at the California Institute of Technology and lead author of one of five articles published in Nature Astronomy.

“As it moves through the interstellar medium” -- the vast expanses of space between stellar fiefdoms – “there's a wave in front, just as with the bow of a ship,” Stone told journalists by phone.

Scientists hoped to answer a number of questions by comparing data sent back by the two probes, which pierced the Sun's protective bubble at different angles and locations.

“We didn't have any good quantitative data of how big this bubble is that the Sun creates around itself with supersonic solar wind and ionized plasma speeding away in all directions,” Stone said.

Particle ‘leakage’

Voyager 2 confirmed, for example, the existence of a "magnetic barrier" at the outer edge of the heliosphere that had been predicted by theory and observed by Voyager 1.

"But contrary to all expectations and predictions, the magnetic field direction did not change when Voyager 2 crossed the heliopause," Leonard Burlaga, a scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and lead researcher for one of the studies, told AFP.

The so-called heliopause is the relatively thin contact boundary where solar wind of charged particles and interstellar wind collide.

Scientists were also surprised that it took 80 days for Voyager 2 to cross this magnetic barrier, while its sister probe did so in less than a day.

And then there's leakage enigma.

As Voyager 1 crossed the heliosphere threshold, it detected particles from outer space -- notably cosmic rays -- racing the other way.

"On Voyager 2, it was just the opposite," said Stone. "Once we left the heliosphere, we continued to see particles leaking from the inside out."

In at least one case, it was a similarity between the two missions that was perplexing.

Johnny B. Goode

"This is very strange," said Tom Krimigis, a scientist in the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University and senior author of a study reporting on measurements of charged particles.

"One crossing (of the heliopause) occurred at the solar minimum, when solar activity is the least, and the other at the solar maximum," he told journalists.

"If we take our models at face value, we expect that there would be a bigger difference."

The Sun's activity waxes and wanes in 11-year cycles.

Built to last a dozen years, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 set out to explore the solar system's outer planets, not to become the first human-made objects to plumb the depths of interstellar space.

After 42 years in action, they are still going strong, although both will run out of power and fall silent within five years, according to the scientists.

But that does not mean they will disappear, said Bill Kurth, a researcher at the University of Iowa and co-author of the study focusing on plasma waves.

"They will outlast Earth," he said. "They are in their own orbits around the galaxy for five billion years or longer, and the probability of them running into anything is almost zero."

If intelligent life in a far corner of the Milky Way finds either probe one day, a "golden record" including drawing of a naked man and woman, bird and whale songs, and "Johnny B. Goode" by Chuck Berry will be on board.

Voyager 2 left Earth's orbit in 1977 a month before its twin Voyager 1, but took seven years longer to reach the heliosphere's outer limit some 18 billion kilometers (more than 11 billion miles) away.

Shaped something like a windsock in a stiff breeze, the heliosphere is formed by the Sun's magnetic field and solar winds that can reach speeds of three million kilometers per hour.

It can be compared to a cosmic supertanker ploughing through space, said Edward Stone, a professor at the California Institute of Technology and lead author of one of five articles published in Nature Astronomy.

“As it moves through the interstellar medium” -- the vast expanses of space between stellar fiefdoms – “there's a wave in front, just as with the bow of a ship,” Stone told journalists by phone.

Scientists hoped to answer a number of questions by comparing data sent back by the two probes, which pierced the Sun's protective bubble at different angles and locations.

“We didn't have any good quantitative data of how big this bubble is that the Sun creates around itself with supersonic solar wind and ionized plasma speeding away in all directions,” Stone said.

Particle ‘leakage’

Voyager 2 confirmed, for example, the existence of a "magnetic barrier" at the outer edge of the heliosphere that had been predicted by theory and observed by Voyager 1.

"But contrary to all expectations and predictions, the magnetic field direction did not change when Voyager 2 crossed the heliopause," Leonard Burlaga, a scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and lead researcher for one of the studies, told AFP.

The so-called heliopause is the relatively thin contact boundary where solar wind of charged particles and interstellar wind collide.

Scientists were also surprised that it took 80 days for Voyager 2 to cross this magnetic barrier, while its sister probe did so in less than a day.

And then there's leakage enigma.

As Voyager 1 crossed the heliosphere threshold, it detected particles from outer space -- notably cosmic rays -- racing the other way.

"On Voyager 2, it was just the opposite," said Stone. "Once we left the heliosphere, we continued to see particles leaking from the inside out."

In at least one case, it was a similarity between the two missions that was perplexing.

Johnny B. Goode

"This is very strange," said Tom Krimigis, a scientist in the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University and senior author of a study reporting on measurements of charged particles.

"One crossing (of the heliopause) occurred at the solar minimum, when solar activity is the least, and the other at the solar maximum," he told journalists.

"If we take our models at face value, we expect that there would be a bigger difference."

The Sun's activity waxes and wanes in 11-year cycles.

Built to last a dozen years, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 set out to explore the solar system's outer planets, not to become the first human-made objects to plumb the depths of interstellar space.

After 42 years in action, they are still going strong, although both will run out of power and fall silent within five years, according to the scientists.

But that does not mean they will disappear, said Bill Kurth, a researcher at the University of Iowa and co-author of the study focusing on plasma waves.

"They will outlast Earth," he said. "They are in their own orbits around the galaxy for five billion years or longer, and the probability of them running into anything is almost zero."

If intelligent life in a far corner of the Milky Way finds either probe one day, a "golden record" including drawing of a naked man and woman, bird and whale songs, and "Johnny B. Goode" by Chuck Berry will be on board.

avapress.net/vdcb0ab8srhb9zp.4eur.html

Tags

Top hits